For the last month or so, I've been meeting with Allyn Burrows at the Somerville headquarters of Actor's Shakespeare Project to run lines. He is opening later this month in the lead role in their production of Timon of Athens.

Timon of Athens has never been my favorite play. My first encounter with it was at age 10 in the Lambs "Tales from Shakespeare" where, after I finished reading it, thought, "huh?" put it out of my mind and avoided it whenever I could.

I'm way north of 10 now but I literally cringed when I heard that Actor's Shakespeare Project, my favorite place to volunteer, was planning a production of Timon. I had just ushered for Othello, their latest show. I was on the bus from Tremont, headed to the Hynes subway with one of the other ushers. Together we griped about this decision. He acknowledged it was one of Shakespeare's "problem children." But he pointed out that he'd never seen A.S.P. do a mediocre production of anything, so if anyone could bring out the best in Timon, it would be them.

I agreed with this point, but silently resolved to sit this one out. Then I was asked to help the lead actor run lines. In spite of my antipathy toward the play, I agreed. By this point (way, way north of 10 years old!), I've learned that if I dislike a play that intensely, I probably have something to learn from it.

Also, as a theatre teacher, having the opportunity to witness an actor's process has been a rare treat. Since I'm primarily a director, working with an accomplished actor has provided me with fresh insights. Allyn did not require me to like the play -- in fact he completely validated my initial reaction to it. But having the text under such focused scrutiny and hearing his insights began to change my attitude. It became like having a mini-tutorial on this difficult play.

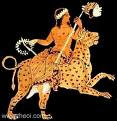

Timon is a challenging character -- a wealthy, generous man who gives beyond his means and is surrounded by false friends.

I started to see some patterns emerge that related to my prosperity training -- Timon gives and gives, but never accepts anything in return, not even repayment that is due him. There is a sense of discomfort with his wealth - he's not happy unless he's feeding or gifting everyone. There are some disturbing declarations about desiring to be poorer so that he would be closer to his friends. As Catherine Ponder often reminds us our reality is created by our words. And when he does become poor, he himself warns his servant to hold a positive attitude. This is all in keeping with a prosperity practice.

Then, for Timon, it all falls apart. It's like a prosperity lesson gone horribly wrong. And more and more, I asked myself, what did he do wrong?

It seems that Timon's fall is not so much from his financial reversals but from his loss of faith. When his friends disappoint him, his trust in humanity is shattered. By the time he finds a fortune in gold, in one of the biggest moments of serendipity ever (literally, since serendipity means finding gold when you're digging for worms - or in Timon's case, roots) he's so far gone in bitterness, he can't even let it in.

And what's funny is that this is exactly how a prosperity practice works -- what we give out returns to us in unexpected ways. The challenge has always been to remain trusting and receptive. Not to man - which is Timon's error - but to the Universe, to Source.

And this is where Timon goes wrong - not just in his bitterness and curses, but also in being closed off from his fortune, not being receptive. Allyn had pointed out that this is a tragic play and I agree that the fatal flaw of the character -- the inability to receive -- is what brings his downfall. He puts his faith in his friends instead of Source and when they disappoint him -- as people invariably will -- he is heartbroken. To me the tragedy is not his bankruptcy but the rejection of his windfall.

At the end, Timon seems to achieve a kind of satori. Even the rage is gone. He has wisdom and detachment.

The production is shaping up nicely -- I went to an open rehearsal today. We saw the banquet scene with Timon at the crest of his wealth and then two monologues from the second half of the play. It was the first time I'd seen it on its feet and I have to say the work was excellent. It's different hearing the lines practiced and experiencing them acted, a revelation of sorts. To actually hear concern for Timon in the voice of his steward, actually witness the unspoken affection between Timon and his former war-buddy, the cynic Apemantus -- the play is taking on a richness for me that it didn't have before. And the unexpected, wild laughter of Timon when he finds the gold was shocking. While the scenes we saw were more or less a "tease-taste" of the production in the works, I could see a strong foundation had been set.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment